Any history buff or liner enthusiast will be familiar with the names of some of the world’s greatest ships. Titanic, Lusitania, Queen Mary, Normandie and United States are just some of these great vessels that have gone down in history as either tragic disasters or triumphs of engineering. But liners such as these may not have been so venerated if the plans of shipping companies around the world had come to fruition. Throughout the 20th Century, vessels were planned, designed, and even partially built which could have rivalled or even eclipsed the most famous of ocean liners. That they remained either plans on a drawing board or a collection of unassembled steel plates is a testament to the unpredictable nature of world events and particularly the destructive nature of the 20th Century.

1) Constitution (1916)

America came very close to building its own superliner decades before the famed United States of 1952. Ironically, the man who designed the pioneering United States was also the force behind a similar, stalled attempt in the early 1900s to spread the stars and stripes across the seas. William Francis Gibbs was fascinated with ships since childhood and despite lacking any formal training, became obsessed with naval architecture and grew up determined to one day design the ultimate ocean liner. Aged 30, he quit his legal career and joined with (some would say dragged along) his brother to design a then unheard of 1,000 ft long ship which he intended to submit to financiers. Essentially enthusiastic amateurs, the brothers Gibbs must have been amazed when both J.P. Morgan and the United States Navy offered to jointly finance their liner, tentatively given the not-exactly-thrilling name of Constitution.

It was not hard to see why Morgan and the Navy were interested in Gibbs’ childhood dream. Constitution would have been an enormous vessel at 56,000 tonnes, and would have more than filled a recent Titanic-shaped hole in Morgan’s International Mercantile Marine company, which had financed the doomed liner. The fact that Constitution seemed to be modelled on (if not outright copied) from the Titanic’s design helped to convince Morgan representatives to sign off on the planned ship after just one meeting with Gibbs. The Navy also saw the advantages of having partial control over Constitution which would have travelled at a staggering 30 knots, a speed which no ship would exceed until 1936. Such a fast ship at the nation’s disposal could be advantageous if the United States were sucked into the war raging in Europe at the time.

It was the First World War which first stalled Gibbs’ grandiose plans. Although a large-scale model was built and tested in late 1916, the USA’s entry into the war in 1917 put a halt on any work relating to Constitution. The Navy’s attention shifted to warship construction and Morgan’s finances suffered as a result of the conflict, putting paid to any prospect of any investment into huge superliners.

Gibbs single-mindedly continued to work on the designs and lobbied for financial support to start work on Constitution. He had hoped that the end of the war in November 1918, and the USA’s new status as a world power would see a resurgence of interest in his beloved superliner. But suddenly Gibbs’ plans became irrelevant; the USA simply seized Germany’s largest liner, Vaterland, as war reparations. Renamed Leviathan, the former German vessel was only a little smaller and slower than the planned Constitution and only needed peacetime conversion to become America’s flagship. A quick and cheap conversion of an already functioning liner clearly outweighed the prospect of building an amateur’s design from scratch.

Gibbs would never give up on his dream of building America’s finest ship and developed his skills as a naval architect over the following decades. By 1950, he had the expertise as well as the passion and was well-placed to again approach the Navy, this time with his design for the legendary United States. Although Constitution had never really progressed beyond a test model, for Gibbs it was a very real project which taught him a lot of lessons, launched him on a path to a career as a successful maritime architect and ultimately, helped to eventually fulfil his childhood dream.

2) Oceanic (1928)

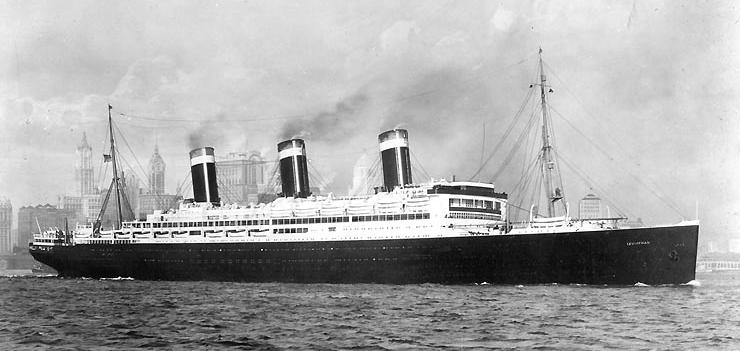

Whilst the fierce rivalry on the Atlantic between ocean greyhounds Queen Mary and Normandie is well known and considered to be the golden age of the liner, it is less well known that the two giant ships were very nearly faced with a third rival. This lesser known third rival also has the distinction of being the only ship listed here on which construction actually began. As a result, White Star’s Oceanic is far more than just a forgotten set of plans and potentially could have transformed the history of transatlantic travel.

Ever since the Titanic disaster, her owners, the White Star Line, had limped along, their prestige and profits severely damaged by the unprecedented tragedy. White Star had lost a large portion of their fleet in the First World War and although the line joined Lord Kyslant’s shipping consortium in the 1920s, it was haemorrhaging money by the middle of the decade. The line’s directors were desperate; only a spectacular new flagship could stave off financial ruin and restore confidence in the company.

Initial plans didn’t tick the spectacular box. The first design for Oceanic (the third White Star ship to bear the name) was essentially a copy of the company’s Olympic – already 15 years old by this point. A second set of designs showed a more radical vessel, with a cruiser stern and squat funnels, but the projected size was only about 51,000 tonnes.

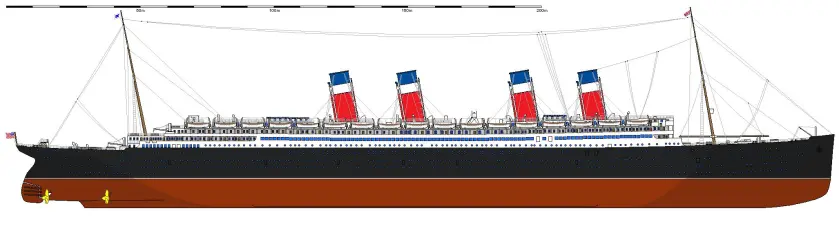

A third set of plans finally gave White Star what they were looking for. Oceanic would retain the cruiser stern and three squat funnels, but would be a colossal 1050 feet long and weigh over 80,000 tonnes. Most significantly, it was intended the ship would have a service speed of 30 knots, and thus able to make the transatlantic crossing in less than 4 days. White Star’s directors, along with the head of the consortium, Lord Kyslant, were elated and placed the order with Harland & Wolff shipyard on June 18th 1928; construction began just ten days later. The date and rapidity of the work is especially significant as it gave White Star a valuable lead in the race to build the world’s greatest liner. Their rivals, Cunard and Compagnie Generale Transatlantique (CGT) were planning vessels of similar speed and proportions to Oceanic. These vessels, which would later become the Queen Mary and the Normandie, were still just sets of blueprints as Harland & Wolff’s workers were busy hammering rivets into Oceanic’s steel plates. It seemed inevitable that Oceanic would be the first of these huge, fast liners to debut and thus dominate the market.

But Oceanic never debuted. It was often assumed that the Oceanic was one of the first high-profile victims of the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The same financial crisis and subsequent Depression would see work stall on Cunard’s Queen Mary for almost 3 years. Work eventually resumed on Queen Mary; Oceanic was consigned to oblivion. The abrupt cancellation of the vessel actually predated the Wall Street Crash and was the responsibility of the ship’s (and White Star’s) owner, Lord Kyslant. Kyslant delayed progress on Oceanic just a few weeks after the ship’s keel was laid, arguing that the vessel should be fitted with diesel-electric engines instead of steam turbines (which he had approved of in the planning stages). After bitter arguments with Harland and Wolff’s exasperated designers, Kyslant won the argument, and wasted almost two months in the process. At the same time, it was discovered that Kyslant’s shipping combine was essentially a massive fraud. A Treasury audit revealed that the combine had been using its vital reserves to pay its directors, including Kyslant himself, generous dividends. Simultaneously, Kyslant had lied about company profits to attract investors. Far from a profitable combine, Kyslant’s shipping empire was utterly bankrupt and at least £10 million in debt. No sooner than the Treasury audit was complete, Kyslant was arrested and later tried and imprisoned for fraud. The revelation that there was literally not a penny left to finance construction doomed the Oceanic.

White Star and Harland and Wolff were able to scrape together additional funds, but not enough to complete the giant Oceanic. As a result, it was decided to scrap Oceanic and scavenge the materials to build two, much smaller vessels. Oceanic’s keel was cut into two, and from the two pieces eventually emerged Britannic and Georgic. Their profiles, and especially their short funnels, give some idea of how Oceanic may have looked.

Oceanic (even if she only existed as a collection of steel girders and plates) represents a great ‘what if?’ in the history of liners. Without Kyslant’s interference and then conviction, it seemed likely that Oceanic would have been completed well before Cunard’s Queen Mary and CGT’s Normandie. With a head start in the intense transatlantic competition, Oceanic may have been able to keep White Star afloat and restore its former glory. It is not inconceivable to imagine Oceanic becoming a symbol of national pride like the Queen Mary later would. Instead, four years after the cancellation of the project, an all-but ruined White Star Line was forced to merge with Cunard and thereafter the company would slowly vanish, as its fleet was gradually scrapped to way for more Cunard vessels. Oceanic was intended as the great renaissance for White Star; instead, she proved to be its downfall.

3) ‘Whale Ship’ (1932)

If Oceanic was a very real project that very nearly came to fruition, the so-called ‘Whale Ship’ was little more than an extremely imaginative pipe-dream. But although the vessel never travelled further than the planning stages, elements of the design were revolutionary would eventually found their way into a huge range of modern vehicles which we take for granted today. The bizarre ‘Whale Ship’ was simultaneously a pie in the sky and an accurate vision of the future.

The ‘Whale Ship’ was the product of the feverish imagination of Norman Bel Geddes. A Broadway musical set designer throughout the 1920s, Geddes opened up his own design studio in 1927. The studio was supposed to focus primarily on small commercial products such as cocktail shakers and radio cabinets. But quickly Geddes turned his studio into a design factory for his ever grandiose flights of fantasy. Geddes and his team began designing various fantastical projects; a bubble shaped car, a nine-deck amphibious plane, even an ultra-modern city Geddes named ‘Futurama’.

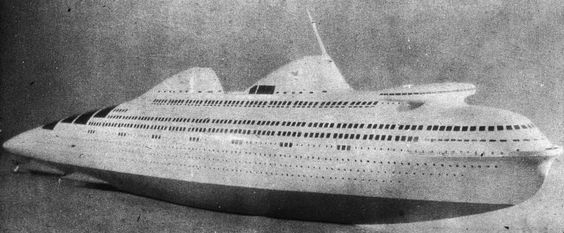

In 1932 Geddes showcased the model of his design for an ocean liner. His design was unlike anything yet conceived and was colossally ambitious. Resembling a giant torpedo more than a liner, Geddes dubbed his vessel the ‘Whale Ship’ due to the two giant ‘humps’ which were actually funnels, and the staggering size his ship would be. The vessel would be 1800 feet long and weigh 82,000 tonnes. Carrying 2000 passengers and 900 crew, the ship would be fast enough to reduce the journey between Europe and America to a single day.

Geddes was under no illusions. The grandiose and fantastical nature concept was unlikely to become a reality. The ‘Whale Ship’ and similar futuristic designs were mostly created to feature in Geddes’ 1932 book Horizons, presenting an art-deco-inspired view of what the future might bring. Nevertheless, the ‘Whale Ship’ captured the imagination of the public during the 1930s. Newsreels and featurettes such as the one linked below showcased Geddes’ model as the ocean liner of the future and took pride in extolling the speed benefits of its innovations.

Pathe 1935: The Liner of Tomorrow!

Geddes’ design may never have sailed, but it did travel to Hollywood. The ‘Whale Ship’ (or at least a model of it) featured in the comedy film The Big Broadcast of 1938. Satirising the intense rivalry going on at the time between the Queen Mary and the Normandie, the film features a similar transatlantic speed race between the fictional ships Gigantic and Colossal. It is no coincidence that the model for Colossal is a carbon copy of the real Normandie, and Gigantic is clearly based on Geddes’ ‘Whale Ship’. Incidentally, Gigantic is shown to win the race, a screenwriting choice which hints at the popularity of Geddes’ innovative design.

Geddes knew full well his ship would likely never be built. What he perhaps didn’t anticipate was that many of the features of his liner would eventually become standard on virtually every form of transport. As can be seen from the ‘Whale Ship’ model, and his other designs, Geddes was obsessed with streamlining. The ‘Whale Ship’s’ hull was designed to reduce wind and water resistance as much as possible. In the 1930s, such aerodynamics were a novel idea. Today, ships, cars and planes are all streamlined as far as possible. In particular, modern trains, especially Japan’s bullet train, owes much to Geddes’ ship design. The ‘Whale Ship’ may have never progressed beyond a series of sketches and a couple of models but it has left an important and highly visible aerodynamic legacy all around us today.