6) ‘The Nuclear Ship’ (1963)

In the heady atmosphere of the late 1950s and early 1960s; amidst the competing themes of sunny baby-boomer-driven optimism and the dark shadow of the potentially apocalyptic Cold War, one force seemed to offer all answers to all people; Nuclear power. Nuclear energy seemed to be the key that would unlock the future. Naively, it was assumed that before long everything would be nuclear-powered; from trains to toasters. In particular it was believed that nuclear energy could revolutionise oceanic transport. President Eisenhower publicly extolled the potential of nuclear-powered vessels and called for the launching of “an atomic ship”.

Early 1960s Britain, basking in the sunny rays emanating from nuclear-obsessed America, began to consider a nuclear-powered ocean liner. Although commercial transatlantic flights had become the norm by 1960, cutting journey times between the continents to hours rather than days, a rather out-of-touch Macmillan Cabinet still felt it was vital to maintain a prestigious British presence on the sea. Seeing nuclear power as the deus ex machina which would restore British maritime dominance and end the silly fad of flying, the government set up a special technical group and handed it £3 million of public money to design the national flagship of the future.

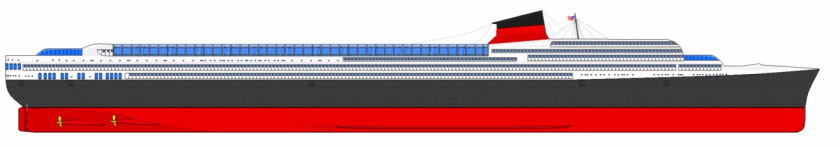

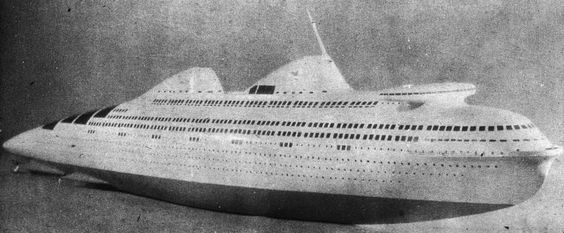

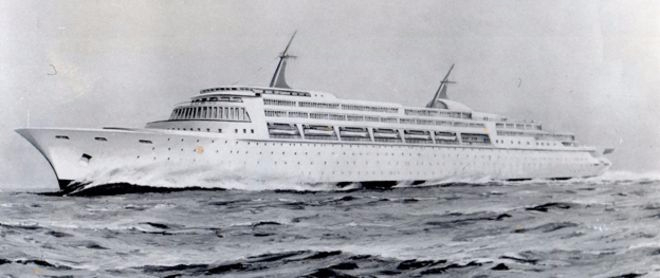

By 1963, the group had spent two years debating the merits of various reactor designs, and had produced a preliminary design for the ship itself. The design of the ship was very similar to P&O’s Canberra of 1961 and seemed to be as futuristic as the planned source of her power; 51,000 tonnes of white hull, aluminium superstructure, swept funnels and fibreglass lifeboats. In Parliament, Macmillan proudly announced that Britain’s ‘Nuclear Ship’ was on the way to becoming a reality.

Then, in mid-1964, an inquisitive MP privately asked the government for a status update on the ‘Nuclear Ship’. He received no reply. Before long it was clear that the whole project had stalled, and had essentially been allowed to wither and die. It is remarkable that the project had lasted so long given the the widening cracks appearing in the once untouchable nuclear edifice. The extreme downsides of nuclear power, particularly radiation had been exposed as early 1958, when the cast and crew of the the John Wayne film The Conqueror had proceeded to die one by one of cancer after exposure to nuclear radiation after filming in the military testing ground of the Nevada Desert. Aluminium-lined passenger ships, carrying over 2000 people, would certainly be at risk. More crucially, the one nuclear-powered passenger ship that was actually built, Savannah, had demonstrated how impractical Britain’s ‘Nuclear Ship’ would have been. Intended to demonstrate the benefits of atomic energy, the American Savannah began leaking radioactive material almost at once, causing havoc for the local environment of the ports the ship visited. In just one year, the ship had released 115,000 gallons of radioactive waste into the sea, as it was only able to store a fraction of that amount. What it could store would always have to be disposed of every time the ship docked. Unsurprisingly, major ports were unwilling to be used as dumping grounds for potentially lethal radioactive waste. Once this had become clear, and once it had become even clearer by 1964 that huge, fast transatlantic passenger ships were costly anachronisms, the British government quietly shelved the ‘Nuclear Ship’.

7) Seawise University (1972)

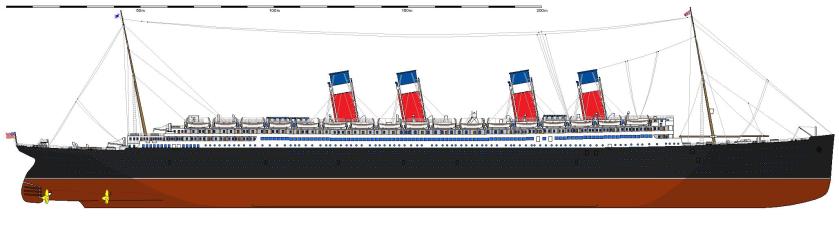

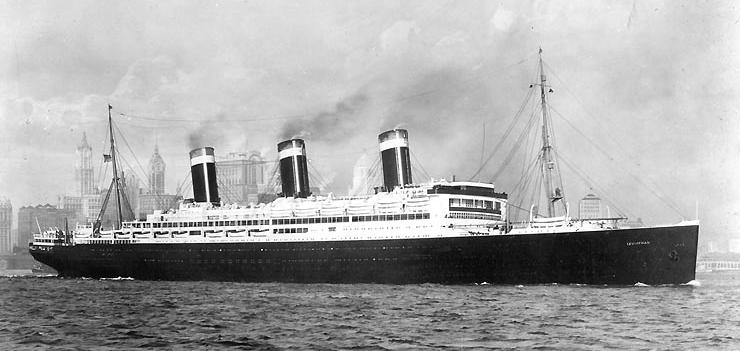

This giant vessel is again technically a cheat addition to ‘Ships that never sailed’. This ship in fact sailed for nearly 30 years, albeit under a different name, different owners, and for a different purpose. That ship was the famous Queen Elizabeth of 1940, sister of the Queen Mary and one the largest transatlantic ocean liners ever constructed. Despite helping to carry millions of American troops during World War Two before going on to provide Cunard with their most profitable years in the 1950s, Queen Elizabeth was a relic of a bygone age by the mid-1960s. The ship carried more crew than passengers, as travellers deserted to airlines, and Cunard retired the ship in 1968.

The 85,000 tonne liner was initially sold to a group of American businessmen, who planned to copy the fate of Queen Mary, setting up the sister ship as a floating hotel in Florida. Quickly losing money, the businessmen put the liner up for auction, where it was snapped up by a mysterious but vastly wealth shipowner, Tung Chao Yung.

A cargo ship owner from Hong Kong, by the late 60s, Tung was looking for a more philanthropic role. Having grown up in a war-torn and semi-feudal China, Tung believed passionately in the benefits of education. He saw the Queen Elizabeth as the perfect means to encourage and spread education, quite literally, across the seven seas. Tung’s plan was simple but bold; he would buy Queen Elizabeth and convert the giant liner into the world’s largest floating university.

The ship was renamed Seawise University, in a particularly egotistical yet strained pun on Tung’s initials; “C Y = See Why = Sea Wise” (….yes, I know). The newly rechristened Seawise University travelled to Hong Kong to begin the conversion process. The ship would be part of the World Campus Afloat (later renamed Semester at Sea program). The programme chartered ships to host a variety of university courses for international students. Courses were to be taught in lecture theatres converted from Seawise University’s former grand lounges and restaurants. Students and tutors would live on board, and go ashore at every port the ship called at to experience local culture wherever the ship docked. Tung was revolutionary in providing World Campus Afloat with a purpose-built, 85,000 tonne vessel (officially the largest ship in the world at that point) with capacity for thousands of students. Such a vessel would revolutionise the idea of education at sea and would benefit thousands of students all over the world. The £5 million conversion was due to be completed, and the Seawise University ready to depart, by February 1972.

Hong Kong residents woke up on the morning of January 9th 1972 to a huge column of smoke blanketing the entire harbour; Seawise University was ablaze. The inferno was out of control, and the huge quantities of water frantically pumped into the ship, destabilised the vessel. Before long, the largest ship in the world had rolled over and partially capsized.

To this day, no one knows for certain what, or who, started the fire. It was known that Tung was a Nationalist, and the shipbuilding unions he had to work with were dominated by Communist Party members. Their mutual contempt was thinly veiled and many have assumed that irate local Communists put Tung’s latest maritime venture to the torch. Alternatively, Tung himself may have been responsible; he had bought Seawise University for £3.5 million, and insured it for £8 million. There is a good chance the mysterious fire may have been an insurance fraud scam by the shadowy Tung.

Had Seawise University been spared the flames, the ship would have likely found itself an incongruous university. The World Campus Afloat programme didn’t attract enough students to fill Seawise University to capacity and the costs of transporting an 85,000 tonne vessel across the world for months at a time would surely have been ruinous. Nevertheless, the programme continues to this day, on a smaller scale, and has benefitted thousands of students over the past few decades. As for Seawise University itself; the charred wreck remained in Hong Kong harbour until being finally scrapped in 1975. Before then, the ship served one final, unforeseen purpose; the setting for the secret underwater MI6 base in the Bond film, The Man with the Golden Gun.

8) Phoenix/America World City (1983)

This final ship that never sailed is essentially what it says on the tin; a literal floating city. The unbuilt ship symbolises the height of 1980s commercial confidence. But the longevity of the project, and its continued development to this very day also suggest that it ironically has a greater chance than ever of becoming a reality.

The idea of having a city built as a ship was the brainchild of the wonderfully named Knut Kloster. A Norwegian naval architect, Kloster had previously taken the revolutionary step of converting the transatlantic ocean liner France into the first large, dedicated cruise ship in the 1970s. By 1983, Kloster was dreaming on an ever bigger scale. His initial design called for a ship that would be a staggering 1,250 feet long, and weigh a truly colossal 250,000 tonnes. With 21 decks (for perspective, the Titanic had just 8 decks), the Phoenix would have capacity for 5,200 inhabitants.

Yes, inhabitants, rather than passengers. Kloster envisioned Phoenix not as a cruise ship or express passenger liner, but as a floating city on which people would live and work. The superstructure was designed almost as three huge apartment blocks; every cabin would be a fully-fledged home. The Phoenix would offer everything a real city could offer. Kloster planned to include dozens of restaurants, shops and boutiques, art galleries, a spa and fitness center, 6 pools, a jogging track 800 metres long, a theatre of 2,000 seats, a casino, a place of worship, a library, a museum, a planetarium, TV and music studios, a university campus, a hospital facility, and a heliport. He also planned to allocate an area for Japanese residents, even providing a special communal garden. The ship would be far too large to enter most ports so Kloster also included several huge lifeboats which could carry 400 passengers each to act as buses, ferrying people from their home on ship to the mainland. With such staggering ambition, and lofty ideals, Kloster proclaimed that Phoenix would be “a cultural spaceship for education, exploration and enrichment, and a global forum for the advancement of international cooperation, understanding and exchange”.

Kloster’s vision was taken very seriously. He had proved himself a success with the France and was the founder of the Norwegian Caribbean Line. As a result, the Phoenix project continued to be developed and designs were perfected over the next few years. At one point a contract was even signed with the American Avondale Shipbuilders. The project began to lag however, as Kloster and his team continually changed their minds of methods of propulsion (nuclear power was once again, briefly, considered). All the while, it became clear just how expensive the project was going to be (an extraordinary figure of $1.2 billion emerged in 1990).

The project gained a new lease of life in 1996 when Westin Hotels & Resorts backed a bid to resume development on the huge vessel, which they insisted be renamed America World City. The new name, and the stipulation that the crew had to be entirely American, was designed to appeal to the US government, from whom Westin and Kloster hoped to gain funding. The project again stalled in the early 2000s, by which time Kloster had retired and the potential funding from Washington vanished with the huge financial drain of the war on terror.

Despite this, Phoenix/America World City is an idea which is still floating (forgive the pun) around. As recently as 2013, a new company, operating under the name American Flagship had bought the rights to the ship’s designs and was lobbying the Obama administration to provide the much-needed funding to start construction. The company made a point of stressing that the ship could be built in sections, across America, providing much needed jobs during a time of economic decline.

With Trump in power and looking for nationalistic prestige projects to rally voters, America World City could once again be taken seriously by investors and politicians. Paradoxically, an even greater reason why the gargantuan city ship may become a reality at last is because it is no longer so innovate, and thus so improbable. Many of the features that Kloster designed, such shops, casinos, spas and planetariums are now common features of modern day cruise ships. Furthermore, size is no longer such a big issue (last pun, I promise). In 1983, the largest passenger ship was still the 85,000 tonne Queen Elizabeth. Last year, Harmony of the Seas was launched, weighing a staggering 220,000 tonnes. As of 2017, Phoenix/America World City no longer seems like such a pie in the sky idea, and consequently has a greater chance than every other ship on this list has ever had, of making the voyage from the drawing board to the ocean.